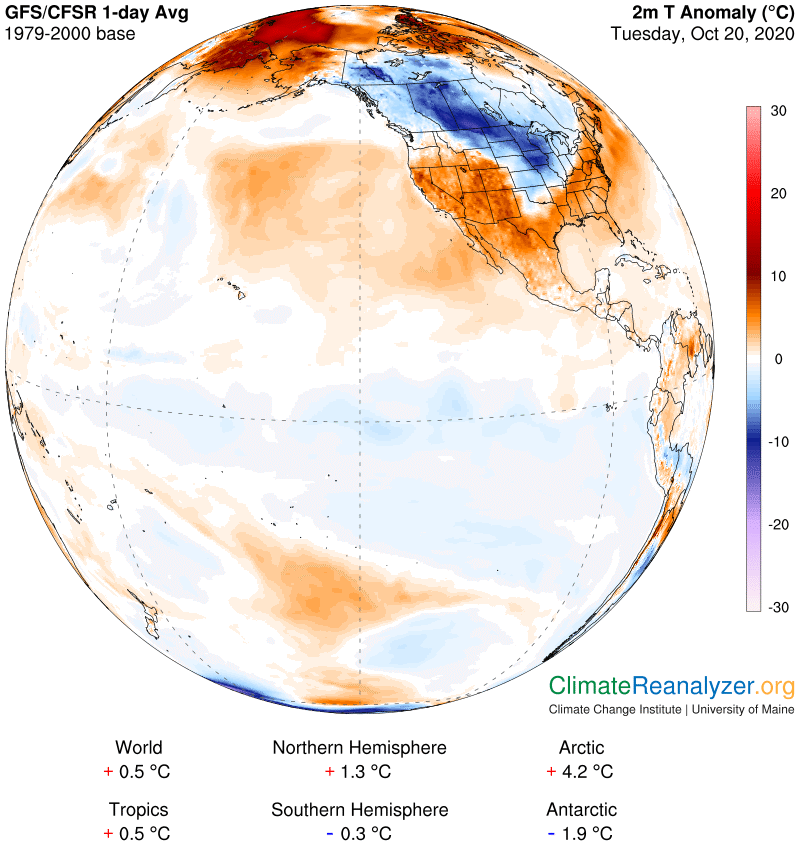

The Arctic heatwave is still in place, and so is the cold anomaly angling downward over North America. This map shows them from a different view than before. My principal intent today is to describe the major water vapor stream arising from the mid-eastern side of the Pacific, which is having an effect on both anomalies, mostly the cold one.

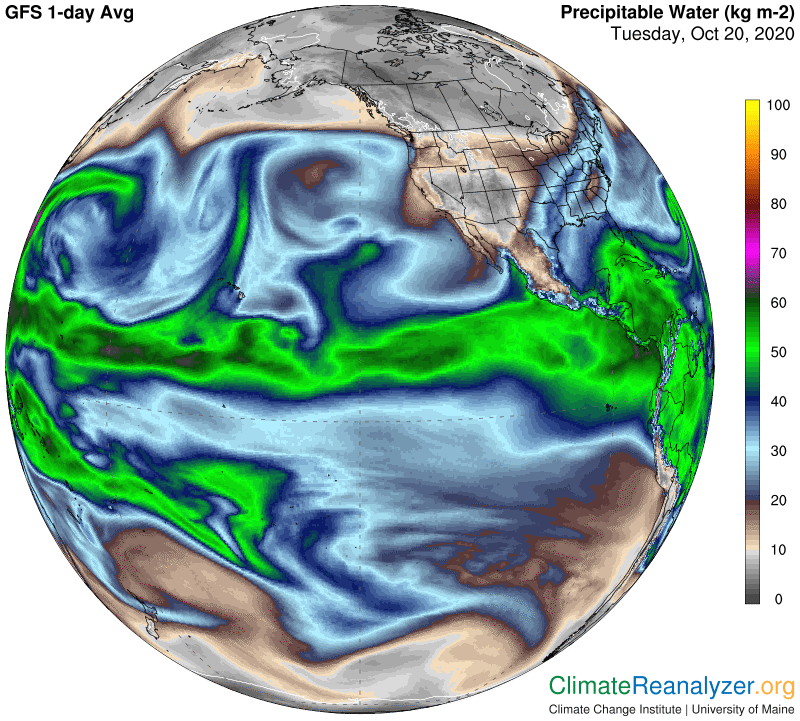

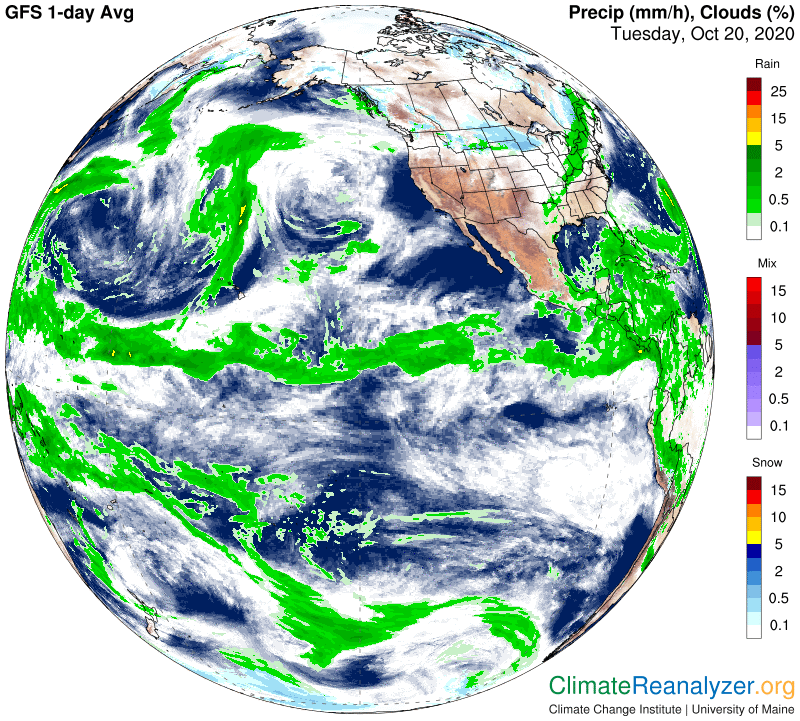

The featured stream emerges from a large area of warm waters around Hawaii. It is seen heading straight north from there, then making a sharp right turn that aims in the direction of Oregon. Upon reaching the Oregon coast it breaks apart, sending some of its remaining vapor northward toward Alaska, a similar amount to the south over California, and the largest portion on to the east and into the heart of the continent.

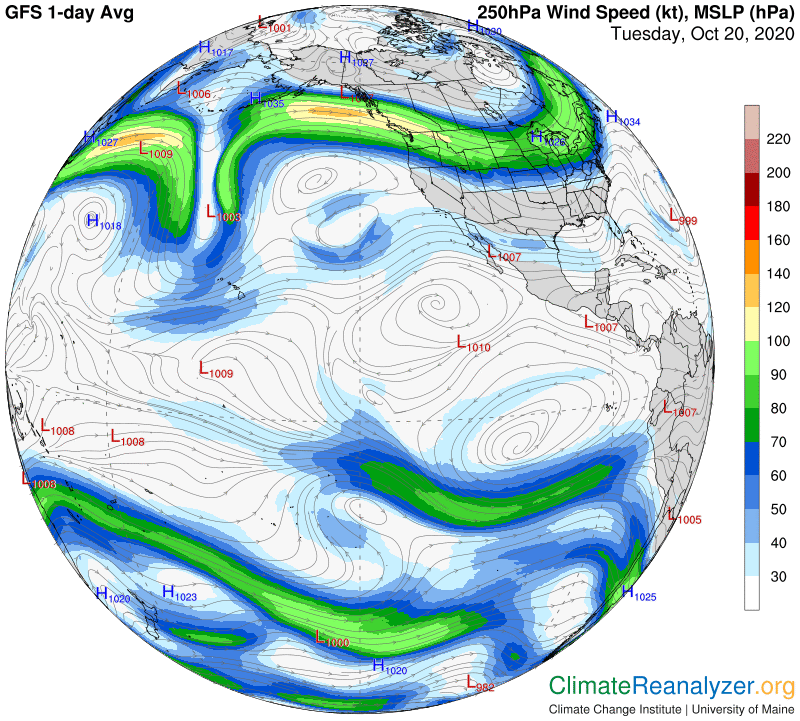

The vapors making up this particular stream were born directly below a massive jetstream wind just as the jet was making a sharp bend in direction from straight south to straight north. These vapors were practically all caught up by the jet and never became independent except for those that escaped when the jet was briefly scrambled above the coastal mountains.

When vapors are picked up and carried off this way by a jet they will naturally tend to condense because of the turbulence. Some will be forming into clouds that reflect sunlight, which serves to cool the body of the jet and encourage further condensation into raindrops and eventually into snow when the jet flies over the continent. The vapor that is able to escape to the north or south without condensing is finally free to exercise its greenhouse powers, now reduced but still considerable.

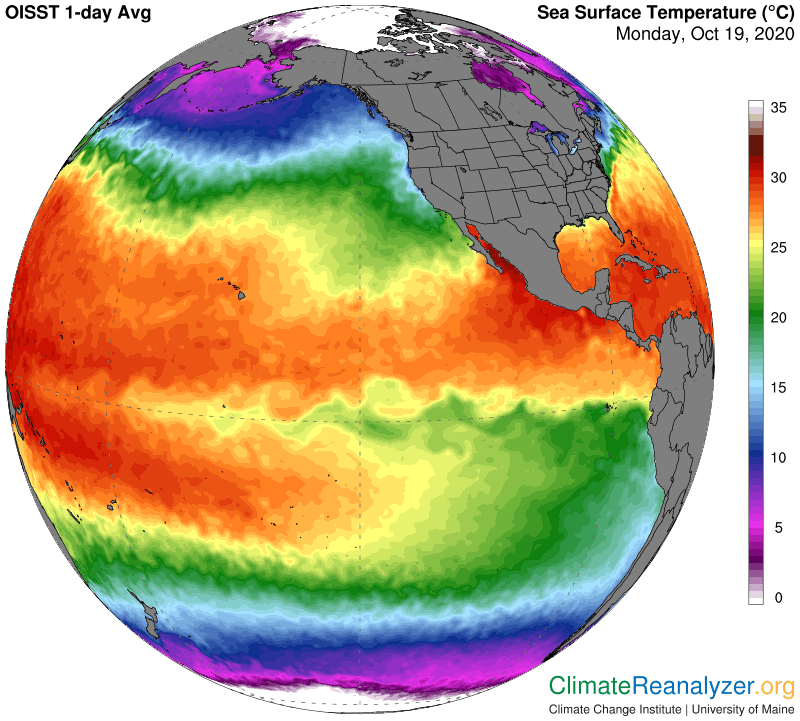

It’s obvious that a substantial amount of vapor has gotten involved in this process, beginning with an adequate source of supply. Fresh evaporation must rise from the ocean surface and quickly be lofted all the way to the jetstream level, a minimum of three to four miles up. All that activity takes a considerable amount of energy, which I believe requires surface air and water temperatures—which are always about the same—of not less than 25C, as well as an absence of obstructing clouds. This map shows how temperatures around Hawaii all make the temperature cut, although not by much within the bulge-shaped zone extending several hundred miles to the north and east.

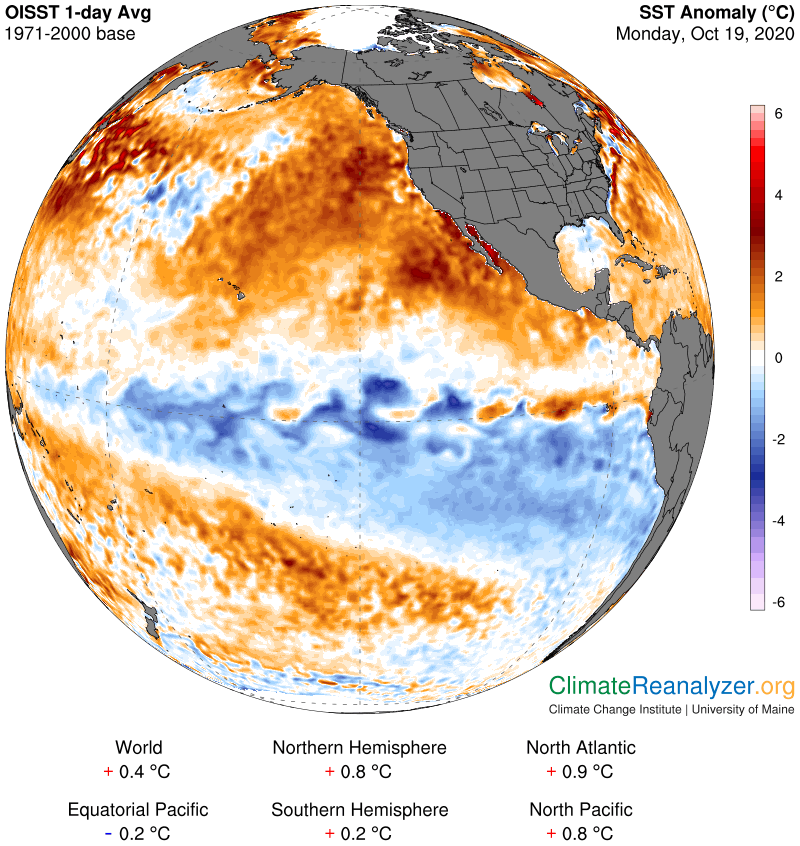

This final map tells us how much the ocean surface in this part of the Pacific has warmed up in just the last forty years. Comparing the data on this and the previous map we learn that large areas of surface that were not warm enough to produce strong high-altitude vapor streams forty years ago are now able to do so. The stream we have just described is one of them, and it has become a prodigious producer, with the potential to become even stronger if the current trend of surface warming continues. When there is no jetstream wind directly overhead its flow would probably be headed at more of an angle that leads toward the continent, introducing an additional source of heat as the main outcome.

Carl