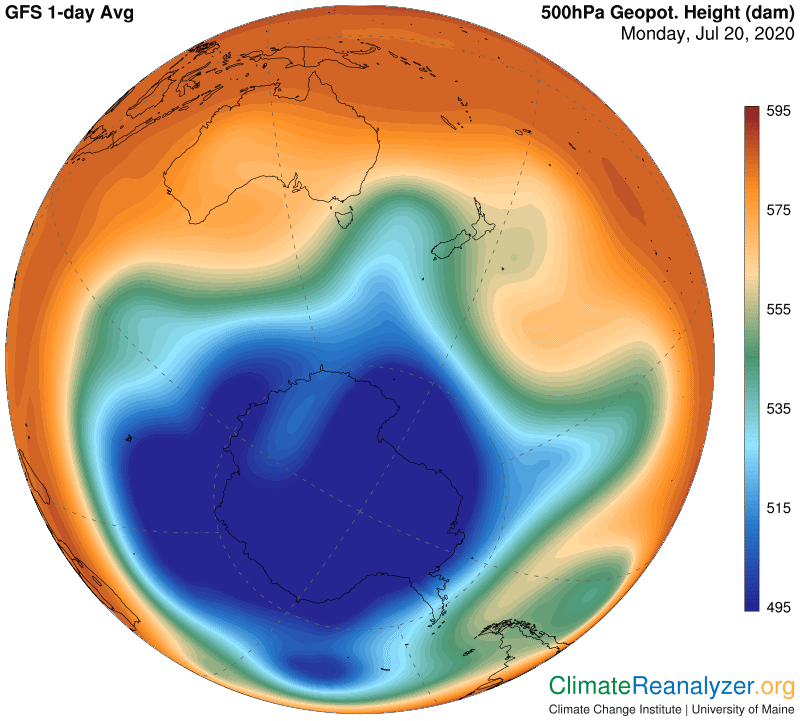

Today I want to revisit Antarctica, just before it starts making the transition away from extreme cold and darkness. It seems odd, but this entire hemisphere is actually the same temperature today as it was on an average day thirty years ago. Its upper atmosphere is currently marked by jetstream winds that are properly positioned and operating st full strength, which gives them great control over weather conditions. That’s the point I want to focus on so we can make comparisons later with what is now happening in the north. Jetstream winds are in turn held under control by the configuration of higher and lower air pressure as it exists in the upper atmosphere, which differs from the patterns close to the surface that we see every day. That map is where we’ll start:

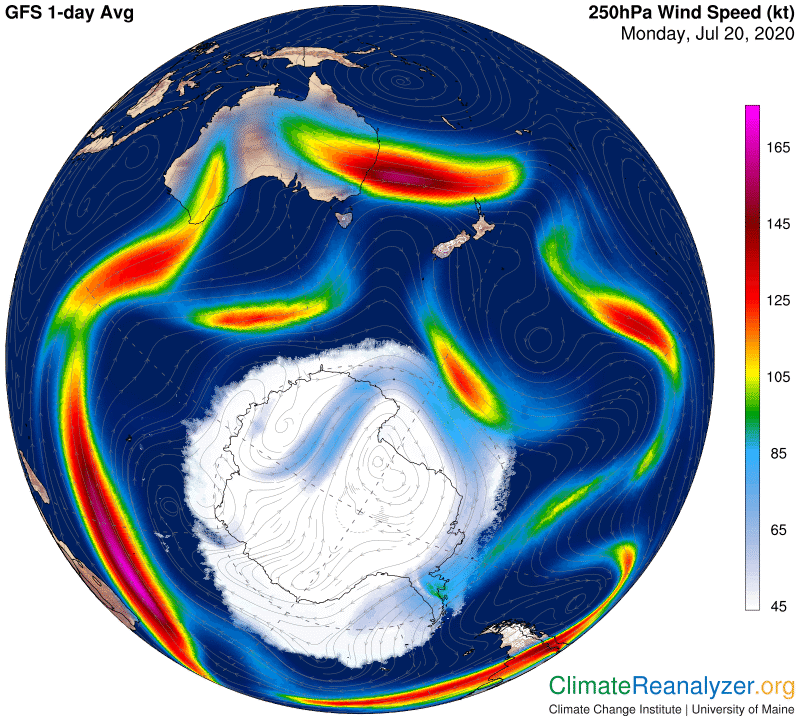

What is most striking is the overall size of the blue zone, which exists as a reflection of Earth’s coldest air temperatures, presently found on the surface directly below. In the north there is currently no such blue zone at all, of any size, mainly because, due to the differences in sunlight received, there is so much less difference between surface air temperatures around the pole and those along the equator. Jetstream wind pathways in both the north and south are regularly created along the contours that divide higher and lower air pressures in the upper atmosphere, as exhibited by the color schemes shown above. As we see in this next image, certain specific contours provide a regular home for each of the major pathways.

I have made a slight adjustment in the way I identify the locations of the jetstream pathways, by putting new emphasis on the existence of strong pathways deep within the interior of the blue zone. These are formed along isobars seen containing any section having the very deepest blue color, which reflects the very coldest temperatures of all at the surface—now around minus-85C (-121F). There is a perfect example of one such pathway in the image, including the isobars and the action of a vigorously strong jet. Along the border of the entire blue zone there is a regular jetstream pathway having winds that are effective even if not especially strong. They mainly become visible when their pathway moves into close proximity with one of the other pathways and the winds of each reinforce one another by creating extra strong jets. The other two major pathways remain as previously described. One of these follows the border of the green zone (or borders when the green zone becomes separated) and the other follows the border of the dark part of the red zone. They are both capable of producing strong jets independently, often covering considerable distances. There is still one more map to look at, showing high-altitude streams of precipitable water, and this is where a number of connections really get interesting.

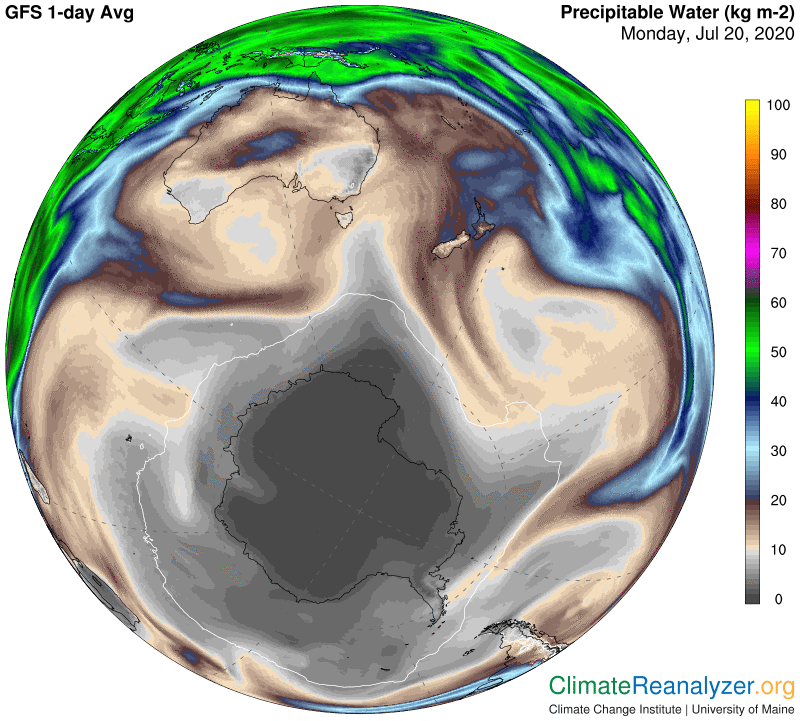

First, notice the existence of a thin white line in the gray part. It represents points where average temperatures are closest to exactly 0C for the day, with everything inside being colder. The shape and size within that line, as you can see, is almost identical to the shape and size of the thin blue line bordering the blue zone we saw in the first image. Think about it. These two thin lines each represent totally different kinds of physical conditions and processes that are separated by over three miles of atmosphere and yet they overlap almost perfectly. It’s not an accident. They do this in tandem, day after day. And now look at the large streams of precipitable water—there are five of them in this image—carrying vapors that originated in tropical ocean or sea waters thousands of miles away and then rose in the form of discrete streams to the same altitude called home by the jetstreams. See how they all have met resistance right at the spot where the blue-line jetstream pathway sits and literally bounce off. Again, this is not just a coincidence. Not much vapor can slip past the winds of that blue line, but when it does—oh boy. Do the air temperatures directly below actually get a whole lot warmer? Go take a look for yourself, or just check out CL #1714 on July 3rd. It happens every day.

Carl